On January 31st, 2020, in my own insular sphere, three momentous events occurred.

A trailer for Fast and Furious 9 was released. Han’s back. That’s nice.

The Senate ruled 49-51 against calling any additional witnesses with crucial information in regard to the misconduct (to use a polite term) of Donald J. Trump. That’s not so nice.

And the final episodes of Bojack Horseman aired.

I still don’t know how to feel about it.

I have refrained from writing about Bojack Horseman for a lot of reasons. Everyone under the sun writes about it, as its cornucopia of obscure pop-culture references, scathing wit, and unflinching, brutal honesty about what can be so fundamentally broken about Us, in every sense of that word, makes it a perfect articulation of the disillusionment of the millennial generation. What could I add, other than another voice to the chorus? Also, as deeply as it has resonated with me, I never had an angle, that urge that simply had to exist. In reality, though, there was only one thing keeping me from writing about this show.

Fear. Fear that whatever I had to say about it, it already said itself. And better. One of the greatest compliments you can give a piece of art.

Now, with its conclusion, I still feel afraid to accidentally tread on its toes. But I do have perspective. And if ever there was a time we could definitively ask what Bojack Horseman is about, it’s now.

So what is Bojack Horseman about? And, warning here, I usually try to contextualize whatever I’m writing about in case you haven’t seen it yet, but that’s not the case here. If you haven’t seen Bojack, see Bojack. It’s worth it.

Is it the story of another broken, hurt man who hurts others in all too familiar ways? A Don Draper? A Walter White? The haunted prestige TV everyman? A guy whose behavior is so bad, it makes the rest of us look good by comparison (yet who we still relate with because we have the same feelings of regret, of shame, of depression and the feeling you just aren’t enough)? Or something altogether different?

So Bad, but So Good

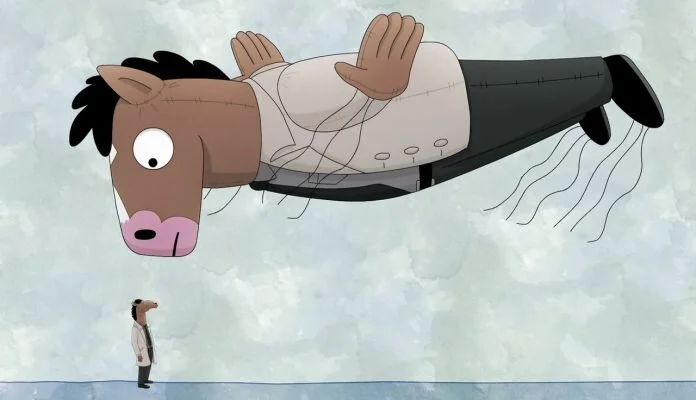

The balloon is the size of my issue with this phrase. The Bojack is my patience with it.

The phrase I find myself continually returning to in how we talk about Bojack is, “It’s so awful and hard to watch, but it’s so good.” What do we mean when we say that? I heard this phrase so often around my college campus, which, as an odd, reclusive East-coast private liberal arts school, was no stranger to Bojack’s unique brand of hyper-clarity, yet total inability to fix his own behavior and how he hurt others. That exact descriptor could fit several people I’ve known.

With this phrase thrown around so much in describing the show, to people who most deeply related to the show, it almost became a truism, a shorthand. An excuse in multiple ways – that while there was emotional pain that show depicted, and indeed, could inflict, (don’t you know, watching traumatizing shows is a form of self-harm, how could you do that to yourself? Or so the thinking would go,) it had an Important message, and was clearly articulated and Meaningful, so the pain was worth it in a soul-searching kind of way, if you’re into that kind of thing. The phrase was also an excuse in that, we framed the conversation so people who didn’t want to see it were totally justified, the same way I might be justified not wanting to see the umpteenth Important War Movie. It might be Important, but it’s painful.

It’s so bad, but so good. The phrase says, “there’s so much good here past the pain. But if you can’t see past it, I get it.”

And I can’t stand it.

It implicitly divvies up and separates the deep pain, trauma, and heartbreak the show depicts, and the genuine emotional catharsis that can come from resolutions, (which are only so meaningful because of this strife,) when in truth, they are part of the same journey. And this isn’t just a college-grad-blog-with-a-too-expensive-education kinda thinking – these are the very basics of compelling drama, of compelling storytelling, and yes, meaningful interpretations of life.

And this particular journey, Bojack’s journey, has been with me through some of the most wondrous and heartbreaking years of my life. From bingeing the whole first season in one AudioVisual office shift because, well, I had the time, and I was curious (HA, what a horrible idea that was), to making a life halfway across the world, to the crestfallen realization, with Diane Nguyen and Mr. Peanutbutter, that I could no longer be with the love of my life. (“I’m just so tired of squinting.”) In a way, refusing to watch Bojack Horseman because it’s difficult is tantamount to turning your back on life as a whole. You can’t have the good without the bad.

I get it, that’s an extreme, almost sanctimonious thing to say. Not everyone is a sad movie nerd who lives vicariously through the shows and movies they watch. People learn these lessons about life through actually living it sometimes. I won’t hold it against anyone who has had their full share of woes without taking on those of an imaginary horse.

But it means something. Going back to that real life argument, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this is a show that most deeply resonates with people who’ve lived lives where their biggest enemies are themselves. It’s not a substitute for experience. It’s a mirror for those with experience. Unflattering. No dressing room tricks of the light. But maybe, just maybe, upon reflection, we see the way forward.

You didn’t think I’d miss a chance to talk Fast and Furious, did you?

Yes, on a horrible day, I would love to just watch the Fast 9 trailer again. John Cena is such a good fit for this series, Justin Lin gives the whole thing a wonderfully serious directorial style that rams right into Susan Sontag’s definition of camp and I really need to write that book, and – for Christ’s sake, a car swings like Spider-Man off a rope! I want nothing more than to stick my head into Fast and Furious land and pretend terrifying, latter-era Roman-republic (not exaggerating) political developments aren’t occurring. But unlike the phrase “so bad and so good” promises, I can’t just divide the bad and the good.

And that’s where Bojack comes in. As the whole. Not as escape, but as a beautiful story that reminds us we can be better.

Bojack Isn’t Better Though

Pictured: Diane realizing what a moral quagmire the entire show is in

I wish there was a different way to write that last sentence, because it sounds so preachy. You know those people who keep arguing for video games and art’s relevance in purely utilitarian terms? You know the one. “Art serves to pass cultural and moral values down through society over time, it’s society reflecting on itself,” blah blah blah. Like all trees-for-the-forest-over-definitions, it’s not exactly wrong, but it does miss the feel of the thing, doesn’t it? Well, let me walk it back from that shitty territory.

When Bojack Horseman first began, it really felt like a slightly more acerbic version of a classic redemption tale. The story of one horse, man, thing, becoming a better person. Sure, Bojack kept digging himself in deeper holes, did shittier and shittier things, but at the end of every early season, he saw a way out. We saw a way out. But at the end of season 5, the light at the end of the tunnel began to fade. Suddenly, we saw there was no way for Bojack to ever completely redeem himself – at least, not in the absolute way we’ve come to expect from our stories.

Because, in between the show’s beginning and end, Harvey Weinstein happened.

That sounds hyperbolic, or like a too-topical reaching-too-far grab in an academic journal or third-rate online blog (wait a second), but it’s the truth. Allow me to mansplain for a second, not because I truly think anyone out there doesn’t know, but for the context and flow of the essay – the avalanche of allegations in Hollywood and other industries fundamentally altered our understanding of capital F capital M Flawed Men. Right? It sounds so obvious I feel stupid writing it, but it’s still worth acknowledging. Suddenly, our sexy Don Drapers and other antiheroes of the TV world stopped looking like fascinatingly complex portraits of pathos and more like -- sexual offenders at best, rapists at worst. Because they are. (In case my politics were unclear up to this point.)

Where does this fundamental shift in realization leave Bojack Horseman? The man who gave a 10 year old girl vodka, who almost slept with his lifelong crush’s underage (well, not in the state of New Mexico, blurgh) daughter, who made a move on his friend’s fiancé, who slept with that same 10 year old at 30 who he had come to see as his daughter?

It leaves him as a piece of shit. (As he happily tells himself.)

You can see the switch flip in season 5. The sickening realization in the writer’s room that if Bojack is totally redeemed by the end, as he’s on course to in season 4, that real people in the real world will use it to justify their own behavior. (See the success of Philbert and Diane’s rants on the world of prestige TV.) That a post Weinstein Bojack needs to face the music. So we get Gina, a real chance at a loving relationship, which ends with him threatening and strangling her. To make an understatement – it’s not fun watching this. It is certainly, by some perverse objective standard, worse TV than the electric season 4 (which may still be the best season in the show overall), but it works. It’s the necessary fall, the only honest outcome for Bojack’s behavior up to now.

By the end of season 6, we have seen Bojack achieve the redemption we always hoped for him, only to “lose it” (I say in quotes only because he hadn’t truly faced the weight of his actions) in the end, and almost lose everything, including his own life. The people in his life we always took for granted, Todd, Princess Carolyn, and most importantly, Diane, won’t even talk to him. Hollyhock cuts off all contact with him, leaving him with the horrible Vance Waggoner, who we see come scarily close to “Red Pill”-ing Bojack multiple times, talking about “PC Culture” this, “the Patriarchy is bullshit” that. By the end of the fourth to last episode, I was just hoping Bojack wouldn’t turn into a Jontron type.

By the end of the penultimate episode, I just hoped Bojack wouldn’t die.

In the final episode, that primal wish, that last gasp “I don’t care how bad his life is, I just want Bojack to live,” is granted, but no free passes are given. Bojack is sent to jail for breaking and entering; he leads a life, but a small, melancholy one. The whole thing has a beautiful “now what?” feel, and a fond farewell to the people that made Bojack’s life, and indeed, the show, worthwhile.

This imagery of Diane isn’t a coincidence.

Beside Every Great Woman is an Okay Guy

It is in these final scenes that we come to realize, as much as this could have been a show about the Struggles of the Flawed Man, it has so much more with such an empathetic, open heart for its entire cast of characters, and such strong, remarkable women who Bojack has formed his life around, who are the real stars of the show (they certainly lead more fulfilling lives by the end).

The final scene with Diane and Bojack on the roof, recalling their first roof talk in season 1, doesn’t recontextualize the show so much as restate its core – the loving, strained, and sometimes outright broken relationship between the two. In Diane’s relationship with Bojack, we reach the show’s core questions. “How do we best treat those we love in our life who continue to hurt themselves and others?” “What boundary do we draw between ourselves and others?” And, to Bojack, who has asked this question of Diane since season 1 and always been disappointed: “Am I a good person?”

That last question haunts us all. After Bojack has done so much wrong, hurt so many so deeply, and after we have perhaps seen our worst tendencies in his behavior – it’s the question the show practically forces us to ask.

Bojack tells Diane he came up just to talk to her, because he likes talking to her. Diane, seeing both how he can think that, but also through to his deeper anxiety, starts talking about the last phone call he made to her before he almost killed himself. How he was drunk (meaning he lied about being sober), how he said he was going to “go for a swim,” that if she didn’t pick up respond he’d know she didn’t care and “go for a swim”. That in those 7 hours between the news that he wasn’t dead and Diane receiving that voicemail, she thought Bojack had killed himself because of her. Because she felt safe enough not to constantly worry about him. That it was her fault. And after learning he was still alive, that he had that horrible power over her.

From the previous episode, we know Bojack’s motivations for calling Diane didn’t come from an inherently abusive place – he called because he wanted to hear her voice. But in how that desire manifested, it’s clear – Bojack made Diane responsible for his wellbeing, his life, in that moment. This betrayal hits harder than all of his previous failings. Not just because it’s so horrible for Diane, who has finally found some sort of peace, but because it encapsulates the troubling dynamic of their entire relationship. As Diane says,

“I wish I could have been the person you thought I was. The person who would save you.”

“That was never your job.”

“Then why did you always make me feel like it was?”

Remember how Bojack and Diane’s relationship first started. He wanted her, possessively, romantically. And us, not knowing any better, likely rooted for him as he’s framed very sympathetically. When that failed, he made her his life coach. For better or worse, it became Diane’s job to give Bojack, not what he wanted, but what he needed. A stable friendship that wouldn’t put up with his bullshit. Sometimes, too often, perhaps, she let Bojack invade her boundaries, but in the end, became a rock in his life. Not the kind that anchors your entire being, but one that gives you the opportunity to stand up on your own. A crucial difference this show understands completely. These are perhaps the most important relationships we have in life, those that set boundaries with us and help us grow past our possessive instincts.

Even in these final moments, this boundary is being defended. The conversation lightens, and Diane refers to Guy as her “then-boyfriend,” as if they have broken up. For the smallest moment, even now knowing how important Diane and Bojack’s friendship as strictly a friendship is, the question is raised: are Bojack and Diane complete enough people on their own to be with each other now? But then I noticed she wasn’t showing her left hand. And sure enough, she soon reveals her left hand, wearing a wedding ring. Bojack starts to feel sorry for himself, jokingly asking if this is the last time they’ll ever speak.

Diane clearly thinks it is. And we have no reason to think otherwise.

I don’t mean to alarm you, Jesse, but there’s someone looking right — at — you

As she gets up to leave, Bojack tells her that he has a “kinda” funny story to tell. And she stays. Soon, words run out, and they simply sit together, sometimes almost looking at each other and moving closer in a shot that’s very reminiscent of Before Sunrise. (Where Ehtan Hawke and Julie Delpy keep missing looks at each other while listening to a record.) While the context is very different, both shots communicate a similar feeling…

“Now what?”

Where Before Sunrise anticipates a romantic union, the final shot of Bojack sees the rest of life coming on. Whether we are ready or not.

The View from Halfway Down

In Bojack’s near-death hallucinations, Secretariat and his father have fused into one being. It makes some sense, as Secretariat was Bojack’s male role model in the vacuum of his biological father, the drunken failed novelist. As dead friends of Bojack gather and start to put on a show, Secretariat scoffs at the process of making peace, saying that his happiest moments in life were on the bridge he took his own life. Staring to the water below, taking in the air. But as the final doorway approaches, a poem he has written says otherwise. He describes “the view from halfway down,” the terror in the knowledge that he is definitely dying, the vain wish to not have jumped.

“If only I had known the view from halfway down.”

Watching the end, seeing Diane and Bojack simply sit there, with an uncertain future, but for the first time a chance to truly move on from their respective traumas, I felt the two characters sitting on a tipping point, about to plunge into the future, or back into the past. Are we at a similar tipping point? Or are we, by 2 votes, already experiencing “the view from halfway down?” Are we absolutely fucked?

Even writing this now, I feel a strange déjà vu, as if I’ve seen this scene in my life years and years earlier. My past self seems to pass judgment on the present– “you’re still thinking about these ideas? These people?” When you spend so long on a certain thought, a certain feeling, or a certain idea – in my case, the complexities of human relationship – you are always at a tipping point of a great new idea; in a much more real way, however, you are just continuing to fall down the same rabbit hole you decided to jump down years ago.

You can still see the moment. You had a crush, and rather than dismiss it as frivolous, you thought to follow that feeling as far as it would go. Not out of possessiveness, but out of belief that such feelings are mundane miracles. That even the smallest love was a form of grace that could always teach you more, that all the ugliness in the world you saw could be avoided if you didn’t try to hold on. What was so obvious then, so quickly decided then, has led you, simultaneously, to the joy that you were right, and the shame that you may have thought of this to curb your possessive tendencies in the first place. A worldview that showed me so many wondrous things but that I’m now trying to grow beyond.

If only I had known the view from halfway down.

Unlike Secretariat, however, I say this not with regret, but with exhaustion, and more than a little awe. And my, admittedly very biased, take on the message of Bojack Horseman is, in the end, a similar exhaustion and awe. A show that has a fierce, compassionate empathy for those who find themselves haflway down, and the belief that we, like its characters, can wake up from the nightmare.

As Bojack and Diane sit beneath the stars, Bojack grumbles, “Life’s a bitch and then you die.”

Diane responds, “Sometimes. Sometimes life’s a bitch, and then you keep living.”