So, in a recent attempt to understand Scott Pilgrim vs. the World better, I read all of the graphic novels. And as much as I always try to come into books and movies with an open mind, I’ll be honest and say I thought I knew what I was in for when beginning this essay. Needless to say, with the result being an essay over 8000 words, I did not find what I expected. This simple, quirky little comic about indie bands, video games, and unhealthy relationships put me down a rabbit hole that I thought I’d never emerge from, as some of my friends can attest. I told everyone who would listen that this would either be fantastic, or my most catastrophic essay ever. Which one is it? You decide! But it all starts with…

Socrates (Again)

In Plato’s Symposium, various stodgy Greek men argue through dialogue the nature of love itself over dinner (as one does after one glass of wine too many). Socrates, Aristophanes, Alcibiades, and other “Es” get together to make “speeches in praise of love” but really just spat and try to come up with the hottest, long-winded-est takes of the evening about just what love really is. For those of you not born in the 300s BC, this was the idle Greek philosopher’s idea of a scathing Twitter thread.

The conversation eventually drifts away from love to some weird Platonic idea of greater Beauty and Truth that sounds an awful lot like religious sublimation—Socrates equates love to some philosophical step ladder in which at the end you have attained totally non-sexual divine enlightenment because of course he does. Yet, before Socrates performs that mic drop on the evening, Aristophanes has a (non-coincidentally) more oft-remembered speech that is far closer to our modern conception of love. He claims that there used to be a union of the sexes—nigh-divine intersexual humans with two heads, four hands, feet, etc. There were man-men, woman-women, and man-women. Eventually, though, the gods split them right down the middle as to have twice the sacrifices—man and woman. These halved souls forever seek each other to die in each other’s arms. In short—our soulmates are literally our missing half.

Leaving aside the queasy-making implications for queer sexuality this argument makes in a 21st century context (because men can clearly only ever romantically love women, right, thanks Aristophanes,)[1] it is easy to see how this portrayal of love affects us to this day, for better and worse. It’s beautiful and comforting to think there is someone that fits you that perfectly, that makes you that content, who is literally your divine-ordained other half, but it’s also scary to imagine never being enough for yourself—only ever being half a vessel. Forever incomplete.

This is the least creepy image of this scene I could find, by the way!

There’s a cute line in Jerry Maguire that is the perfect modern articulation of this thought—we all remember it. Tom Cruise has come over to Renée Zellweger’s place to win her back, he’s making all the usually gossipy divorced ladies in the house go “aww” at his sweet, romantic gesture, and from across the room, he says, “You complete me.” It’s an incredible line, to be sure.

It also happens to be the one of the most insidious ideas we have ever had as a culture.

Scott Pilgrim Take 1

When I first saw Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, I absolutely adored it. I hadn’t actually dated any human being at this point, like any self-respecting antisocial misanthropic middle/high school mankin,[2] but I fell in and fell in hard with the ethos and romantic message of the film, especially the anti-hero characterization of the titular Scott Pilgrim. For those who are unaware, the film follows Scott Pilgrim through a magic video-game-tinged reality where he fights the seven evil exes of his new girlfriend Ramona Flowers, while also coming to grips with being kind of a shitty person and how he can change that. I loved the nonstop game references and whipsmart visual gags, for sure, but what pushed it over the edge for me was the fact that the film actively acknowledged what a flawed person Scott was. Here was a rom-com where the protagonist was absolutely in the wrong in many ways, who had to better himself before blindly leaping after the girl. Yes, 23-year-old Ari knows there are many films that do this better (and we’ll even talk about one of them!) but 14-year-old Ari’s mind was blown, okay?

That being said, even 14-year-old me knew that what the film was trying to say, and what was actually being said were in almost outright warfare with each other, that there was something kind of weird about a guy fighting seven video-game bosses to get the girl as a reward at the end with next to no earned relationship between the two. The final message, that Scott and Ramona are both flawed people but overcome these flaws to bravely grow together and not run away, resonated with me, even as I saw that these people really had nothing in common and kinda sucked together. It was the thought that counted, right?

Well, no, because at the same time I was coming to this conclusion, other ardent fans of the movie were insisting that Ramona was simply the wrong girl. Clearly, Scott should have kept dating the 17-year old Catholic school girl Knives Chau, right? Yeah, he’s 23, and yeah, she’s a high schooler, and yeah, it’s a fucking felony, but she likes video games just like he does! She’s a gamer girl! We’re all teenagers in 2010 and think the concept of an Actual Woman who likes games is a near-divine concept! Eat your heart out, godly intersexual beings of Aristophanes’ speech—the Gamer Girl is the real divine providence here! If you think I’m joking, here is a Real Internet Review of this movie from 2010:

Just to recontextualize, some quotes:

“A lot of you have already argued, that, hey, that’s the way the graphic novels are, the beginning of them is [sic] boring, stupid, and uninteresting, but you know what, this is a movie, I don’t care if it’s the way it’s supposed to be!”

“…Knives—who, by the way, I don’t know if anybody’s with me on this, but I’d rather be with Knives than Ramona. That’s just me… he lusts after Ramona. And then you ask yourself, why? Ramona is uninteresting, she’s not even really that hot… but then you realize that was the point of the movie. You go into movies expecting a certain thing, that would be like putting a tragic end into [this movie]… Sure it might be more profound and you’re saying a message…but it’s not a message that we want to hear… They will desire a different ending… Ultimately he has to make a decision between Knives and Ramona. He goes with what you think he’ll go and it just doesn’t seem right, especially when one of them is his true soulmate.”

Wow. Now, I admit I felt a little bad calling this guy out so baldly, and I might be cherry picking a bit because I’m sure not every fan (#notallfan) had this, honestly juvenile and entitled reading of the film, but this was absolutely the general tenor of the conversation around the movie. “Finally, a good video-game movie that all self-respecting nerds need to see! Kickass action! Boring talky bits with boring messages we don’t want to hear boo!” So, sorry, not sorry Angry Joe. But, as awful and misplaced as his argument is, he is reacting to a genuine emotional disconnect in the film. A lot of us did. It’s just one he did not articulate, one that he couldn’t. One, that, honestly, I couldn’t either. Not at 14.

Like Scott, we—and by we, I mean socially anxious, entitled, white “nice guy” gamer boys who put women on a pedestal and blamed anything but ourselves for our distance—had a lot of growing up to do. And like Scott, we kinda got away with not, despite lip service to the contrary. But we were about to lash out in embarrassingly public fashion, in an event that would change our perception of “gamer culture” forever, and maybe, just maybe, lay the groundwork to someday elect a racist orange as President of the United States.

And Scott Pilgrim is partly to blame.

Scott and Ramona, realizing this is going to be one of those posts…

Gamer Gate

In 2014, Zoe Quinn, an independent game developer who had the gall to be a woman in the field, broke up with a man named Eron Gjoni. This man proceeded to post a lengthy diatribe on Wordpress named “The Zoe Post” in which he essentially did the thing all frustrated, dumped men do, which is spit vitriol to whoever will listen. He accused her of infidelity, among other things, and was quickly banned from most reputable sources (Penny Arcade, Something Awful, among others), but his Wordpress post was shared onto 4chan’s forums. In case you haven’t had the displeasure—4chan is reddit but as an infinitely deeper cesspit full of involuntary celibates, Neo Nazis, and more! It’s a fun place. This more sympathetic audience created the name of their movement, all in the interest of defaming this one woman—“GamerGate.” This group of balanced individuals proceeded to begin a harassment campaign against Zoe Quinn and anyone who spoke out against them, claiming they were acting in the interest of “Ethics in video game journalism”, since Quinn slept with a journalist and that was clearly the only reason she got positive press on her game, right? (Coughcough we think all women are sluts and want to hide it behind lofty language about the ETHICS OF VIDEO GAME JOUR— sorry can’t finish that with a straight face.) This debacle continued for almost 2 years, as the very same people throwing misogynistic insults and death threats at women in the game development scene also created new accounts posing as feminists and progressives also against Zoe Quinn. Families were harassed, addresses leaked, death threats sent by the thousands, and guess who supported and fanned this free-thinking fire? None other than Milo Yiannopoulos, alt-right firebrand; or, if we’re not using euphemistic normalizing Newspeak—racist, sexist, bigot who got promoted to the head of Breitbart’s tech division for his actions during GamerGate! Yeah! GamerGate’s weaponization of the trolls of the internet was the groundwork for greater disinformation campaigns during the 2016 Presidential Election, and we all know how that went!

Okay, deep breaths.

For an actually in-depth and far more terrifying look at these trends, please take the time to read this fantastic article by Dale Beran on 4chan’s connections with the rise of Trump, and this timeline on the events of GamerGate. It’s overwhelming, it’s exhausting, it’s depressing… but it’s important to understand.

Now, just a few paragraphs earlier, I said Scott Pilgrim vs. the World was partly to blame for this mess. That’s a little harsh. I don’t blame Edgar Wright,[3] the director of the film for electing Donald Trump. That would be ridiculous. What I do lay at Scott Pilgrim’s feet, however, is the continuation of normalizing women-as-rewards specifically for a gaming-oriented-audience.[4] Because 14-year-old-me was right in one respect—the film empathizes with and articulates Scott’s (and therefore gamer men’s) struggles and worldview with incredible precision. The same cannot be said, however, of the women of Scott Pilgrim, including Ramona.

Especially Ramona. And this discrepancy damn near sinks the whole film.

The more you know: this wasn’t even a take, Michael Cera was just staring at Mary Elizabeth Winstead like that and they decided to keep it.

Scott Pilgrim Take Two

Originally coined by A.O. Scott to describe Kirsten Dunst’s character in Elizabethtown, and her total lack of interior character with the sole purpose to make Orlando Bloom’s life more quirky and interesting, the term “manic pixie dream girl” has since caught on like wildfire and been used to death (or are women in film simply underwritten? [the answer is yes]), but there is no better way to describe Ramona Flowers’ character in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.

“We’re so quirky!”

Throughout the film, she and Scott have no chemistry, and Mary Elizabeth Winstead’s (great) performance leads us to believe that she has no interest in him whatsoever. Every step forward as a couple between them feels less like enthusiastic consent between equals, and more like begrudging admissions extracted through coercion. Take, for example, the scene where Ramona delivers Scott’s package, and Scott uncomfortably keeps her there and refuses to sign for his package until she agrees to go on a date with him. Even the cinematography suggests something deeply uncomfortable is occurring here, as Scott is pushed up close into the frame and against the door, while Ramona is instinctively further back in the frame as if wanting to back away. He is imposing, she is diminished and passive. The final line of the scene, “If I say yes, will you sign for your damn package?” certainly doesn’t scream romance.

This is not an unusual feature for romantic comedies—plenty of films feature reluctant heroines being pushed by headstrong men who can’t take no for an answer (that’s a whole other essay). His Girl Friday gets great mileage out of this dynamic, making it the engine of the film’s dramatic structure. Bringing Up Baby even pokes fun and inverts this dynamic, with Katharine Hepburn badgering a poor Cary Grant until he falls in love with her, and we can’t help but ask if it is truly a newfound zest for life or Stockholm Syndrome. The key difference, though, and why Scott Pilgrim fails with this attempted dynamic, is that His Girl Friday knows this courtship is problematic. Cary Grant plays Rosalind Russell’s ex, and a slimy ex on top of that! As he schemes and manipulates and draws her deeper into bad old habits, we have fun seeing him go to work, and so does she. But we are also made deeply aware that this is unhealthy. In that paradox, there is a tension that drives the entire movie forward. Scott Pilgrim has no such nuance. We do not see Ramona have fun with Scott, we just see him moon over her as she inexplicably keeps dating him. Without that mischievous His Girl Friday energy, we are not co-conspirators to a thrilling affair—we are witnesses to a yowling cat being dragged by its tail as it sinks its claws into the ground in vain. It’s not fun. It’s just kind of awkward and uncomfortable.

Perhaps worse is Ramona’s eventual admission that Scott is “the nicest guy she’s ever dated,” despite him being characterized as an absolute bastard by everyone else in the film. Even Scott himself admits, “That’s kind of sad.” In defter hands, this would be the launching point for greater introspection, but the film doesn’t develop this further, instead treating it as the catch-all for why Ramona is with Scott, inadvertently validating every “nice guy” bullshit argument men have ever had.

Ramona’s only potential moment of agency is in breaking up with Scott for how he has treated her thus far—a time when she can put her foot down and say she deserves better, or has her own life to get to. A My Fair Lady moment, if you will. But while she does break up with Scott, she does so to go back to her ex Gideon who she’s never really gotten over (not great), and it is later revealed that she was actually being mind controlled by Gideon at the time, so this was never her decision to begin with. At least Audrey Hepburn chose to take Rex Harrison back.

After the climactic fight with Gideon, the biggest, baddest, evil ex of them all, where much ado is made about Scott earning the “Power of Love”—no wait, now the “Power of Self Respect”, we see him draw a flaming colored sword from his chest on both occasions—Scott asks if he and Ramona can get back together, and she says yes, despite him not having grown as a character at all. He still cheated on Ramona and Knives—he may have admitted it, but he never meaningfully made it up to them. The change is symbolized and signaled, but… it never actually occurs.

Perhaps no moment is more indicative of Scott’s stasis than his confrontation with Nega Scott. After Gideon is defeated, the soundtrack goes quiet and we hear Gideon say, “You can defeat me, but can you defeat… yourself?” And from the ether appears a black-and-white Scott with red eyes, a symbol of his own demons and all the ways he hurts himself and those around him. It’s classic shadow self stuff, but it’s a great opportunity for Scott to visually (for film is a visual medium, after all) confront his worst self and demonstrate change to the audience. In Hero’s Journey terms, this is the Return Home, where we’ve been told the character has grown, but we need one last test, one last crucible to see it for ourselves and really believe it. Given that 95% of the movie has built up how flawed Scott is, we especially need this scene. Ramona and Knives offer help, but Scott refuses, saying he has to confront this alone. The anticipation builds, Scott and Nega Scott are framed opposing each other in profile on the screen, a video-game announcer bellows, “Solo Round!”, and…

We cut to Scott and Nega Scott walking out the front door, chit chatting about brunch and waffles, with a lunch date set for next week. “What happened?” Knives asks. “Oh, nothing, we just shot the shit. He’s actually a really nice guy!” Scott replies.

…

…..

I cannot overstate my disappointment with this conclusion. An earlier draft of this had me saying, “You motherfucker!” but that felt a bit dramatic. Let me explain slightly more calmly. This is a cheat. This is a moment that is tonally appropriate and cute in the moment, yet one that undermines the entire dramatic foundation of the movie. We have spent the entire film shitting on Scott. Literally every other character in the movie has taken him to task for being an insensitive, selfish, cheating bastard. Kim, his ex-girlfriend and drummer in the band constantly calls Scott “scum” and it never gets old. Julie, his acquaintance/enemy frequently cusses him out and calls him a “wannabe ladykiller jerky-jerk.” His roommate Wallace says to Knives, “You’re too good for him. Run.” His sister Stacy… you get the idea. We have so much great dialogue and so many hints from the supporting cast suggesting that Scott is going to get his comeuppance… but he never does. All of these consistent, albeit shallow characters are relegated to little more than lampshading[5] for Scott’s bullshit, giving us the impression of a world with consequences and change when none really exists. “We get it,” the cast of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World says. “Scott sucks.” This self-awareness buys faith with the audience for much of the film, but by the end—when Ramona still chooses to be with Scott, when all of his friends rally behind him to defeat Gideon, when Knives still likes him despite cheating on her—it’s rendered entirely ineffectual.

And so, for this visually beautiful, hysterical, frenetically paced, perfectly directed, edited, and performed navel-gazing weaponization of gamerdom and the angst of self-absorbed men, there really is no more perfect ending than Scott confronting his darkest self, and saying “Okay! Nothing wrong here! I’m awesome!”

Video games are awesome, Scott Pilgrim says. You’re awesome for liking them, Scott Pilgrim says. There is nothing wrong with you. And women? They’ll come to you. Eventually. Why? Well, we don’t really know.

High Fidelity

While Scott Pilgrim has quite a few problems, High Fidelity takes a very similar premise and crafts one of the greatest romantic comedies of all time from it. Starring a latter-day, comically jaded John Cusack, the film follows Rob Gordon as his girlfriend Laura has just broken up with him and is leaving the apartment. In an immature power play, he yells after her that she is not even in his “top 5 worst breakups of all-time” list, and may only barely sneak into the top 10. “If you really wanted to screw me up, you should have gotten to me earlier!” he yells from his window.

From there, he goes down memory lane, remembering and eventually contacting his 5 biggest exes, arguing with his coworkers at his record store and navigating his awkward new standing with Laura along the way. It’s a premise that could easily become aimless, but the stellar script and Cusack’s fourth-wall breaking keep the exposition-heavy first act light. As he recounts his most memorable (or traumatic) romantic experiences, we get the sense he is not an amazing guy. He broke up with his high school girlfriend Penny because she wouldn’t let him touch her breasts while making out, or have sex with him. He reacts to every misfortune and dumping in his life as a personal slight, marking himself “doomed to be rejected.” At the end of the first act, our opinion of Rob is solidified as he lists, finally, just what he did to make Laura leave. He cheated on her while she was pregnant, borrowed money from her and never returned it, and even mentioned that he was looking for other people while dating her. It is here that we also learn, perhaps unsurprisingly, that Laura is the true number 5 ex on his all-time list. Perhaps sensing the audience turning against him, he narrates, “Did I do and say all those things?” “Yes,” a conversation between Laura and a mutual friend interjects. “No!” the mutual friend proclaims in shock. “Yes.” Rob confirms, looking the camera dead in the eye, Cusack’s natural charm taking a sharper, more caustic edge in the moment. “I am a fucking asshole.”

I needn’t mention that this is a greater level of self-awareness than Scott Pilgrim mustered, but it goes further from there, putting Rob on a truly deserved redemption arc. He messes up, he has flaws, and he even gets worse from Act 1 onward for a bit, but he learns from his mistakes and gets on the path to becoming, maybe, just maybe, a good enough man for Laura. It helps that High Fidelity has one of the most dryly funny scripts I’ve seen, poking fun at Rob’s tendencies. In one scene, after being dumped by his college girlfriend Charlie, he yells, “Charlie, you fucking bitch! Let’s work it out!” In just two sentences, the movie perfectly cuts into the paradox and intense emotions of breaking up, and it displays this insight again and again. By the end of the movie, with Laura back in his life, and everything seemingly perfect, Rob almost cheats on Laura again on a whim—and realizes that he is his own greatest obstacle. At the end of the film, Rob states, “I’m making a mix tape for Laura. Full of songs she’d like. For the first time, I can see how that’s done.” At the end of his journey, he escapes his own rabbit hole of memories, his self-centeredness, and sees Laura as her own human being, in direct contrast to Scott and Ramona.

Of course, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is not an original story—it is a film adaptation of a graphic novel. In doing due diligence, I had to read the source material, which is not only different, but addresses many of my concerns…

But that only raised more concerns.

To hint at the problem:

I may think Rob is worthy of redemption, but that is far from the only valid reading.

Philadelphia, 2017

On a sweltering June day, Diane and I sat down next to each other by a window seat in the train to the northern suburbs, uncomfortably fidgeting. In five days, we had still not become fully settled in each other’s presence. It was understandable. We had only just kissed for the first time five days ago since my plane from England landed, and this was the first time I had occupied this much space with someone for such a prolonged period. I sat stiff by her side.

I felt it was nerves and inexperience. She felt I was distant and didn’t want to be with her. I would learn that part later.

“So, what did you think of the movie?” I asked.

“It was fine,” she shrugged.

“I think High Fidelity is an interesting counterpoint to Say Anything. Like, Say Anything is so idealistic, it’s almost unrealistic. But in High Fidelity, John Cusack is such a flawed guy, and we get to see him grow up.”

“I guess. I’ve just known too many guys like that.” she replied.

Tumbling Memories

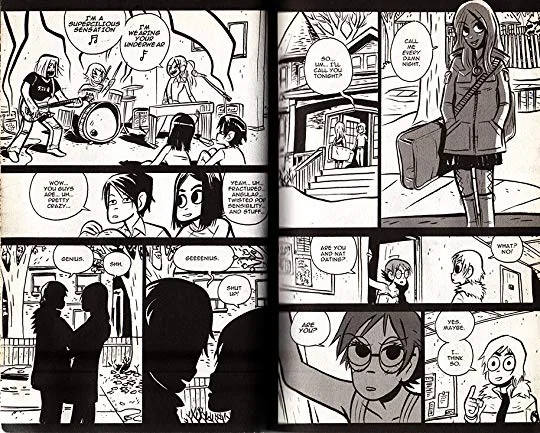

Unlike the film, the Scott Pilgrim graphic novels have an eerie, dreamlike quality as present events and crucial flashbacks blend into one other without warning. Even in the comic’s most straightforward moments, time rarely moves reliably—the turn of a page can take the reader forward one second or one hour, with no obvious cues as to when we have jumped to. Scott and Ramona’s own sordid love histories are drawn in far more detail, as Scott in particular dreams his flashbacks, only to have Ramona intrude in the present day, begging him to wake up.

Between this and the darker color palette of the comics—seriously, look at some full color screenshots, and note how much grimmer the ambience is compared to the film’s cheery hues—there is a strange feeling of dread that accompanies each page. Knives is now a tragic figure, with the comic taking time to notice her alone on rooftops, with her ex Scott nowhere in sight (something rarely afforded the character in the film). The story is much franker about the angst of 20-something existence, as the characters are all trapped in a sort of perpetual ennui about finances and their futures.

Ramona herself is more characterized and fully drawn in as a person. With no runtime constraining the story, we see more of Scott and Ramona just being together—you know, having fun, actually seeming like they like each other. Ramona is still a manic pixie dream girl, but we see what the original intention for their characters are—smitten, but deeply hesitant, wounded, and uneasy from past experience. Not all of Ramona’s characterizations are flattering—unlike the film, we get a genuine impression that she’s pushing Scott away and has a teetering relationship with substances.

The middle section of the series, especially, is permeated with a sense of growing dread as Scott and Ramona’s distance and sniping grows more and more pronounced between bouts of confronting evil exes. Ramona, having cheated on all her previous partners, suspects Scott of the same with others. She is disturbed by Scott’s relationship with Envy Adams—who takes a much more blatantly antagonistic role in the story of the comic—seeing it as a sign that perhaps Scott might not be as sweet as he seems. Who we choose to be with says something about us, after all. The end of the second act turns the screws especially tight, as an ex sleeps over at Ramona’s place, and she misinterprets how Scott slept at an old friend’s house. All hell is about to break loose, when Scott finally tells Ramona that he loves her. Shocked, she says she loves him too, and they embrace. In that moment, we understand the uneasy pact they have made (as well as why they are together):

These two are each other’s only hopes of being understood. They have agreed to accept in each other what no one else will. With all the good and ill that promises.

England, 2017

Earlier in the year. I curled up sideways into my blanket, my laptop propped up on my nightstand. On the screen, Diane lay on her side, softly, sleepily smiling.

“Is there anything you want to say? Anything you might be saving for Philadelphia?” she asked.

“I really want to say it.”

“I think I know what you’re talking about.”

I laughed. “Yeah, gee, I wonder what it could be?”

Diane went silent.

“I love you.”

I paused for a moment, the words clear in my head, but heavy on my tongue. I meant them—that’s why they carried enormous weight.

“I love you too.”

The Glow

Ramona’s character, in the film and to a lesser extent the comic books, is defined by a vague sense of guilt that forces her to always run away from her problems. “I’ve dabbled in being a bitch,” she says, alongside “My last job is a long story filled with sighs.” Like Scott (as evidenced by the erratic, constantly flashing back structure of the comic), she is seemingly forever trapped in the past. She keeps her feelings close to her chest—and by close to her chest, I mean they are very obvious but she often refuses to communicate them.

A huge difference from the film is Ramona’s tendency to glow whenever memories from her past are triggered. Any time she starts to glow, you know the current proceedings are going sideways and quickly. By the end, we learn that this glow is associated with her self-hatred—a power that simultaneously lets her become incredibly powerful at points in the story while also hurting herself, and indeed, being entirely fueled by self-loathing, you can’t imagine that’s healthy.

While there is a mind control storyline in the comics, it’s subtler than the film. We learn Gideon has implanted himself in people’s minds, influencing people’s decisions rather than outright controlling them. It does put the comic in a bit of an interesting bind, as it has to draw the lines between: Scott’s power, Ramona’s glow power, Gideon’s mind control power, what effects what and how this mythology all really works together. In the ending battle, I was enthralled (especially since Ramona got to kick Gideon’s ass herself), but also very lost as to the particulars of the supernatural abilities, and sort of just letting it all wash over me. This is a shame, because up to this point, all of the powers and moments had very specific metaphors for the real world, and the comics lost an important moment to make a clearer statement in the confusion. That being said, I won’t complain too much. Ramona, rather than going to Gideon when leaving Scott, goes to her parent’s place to be by herself—of her own free will! There’s even a great “gotcha” moment where Scott goes, “But I thought you had her!” and Gideon says the same.

Also telling is how much better handled Nega Scott is in the comics. Nega Scott appears as a physical manifestation of all the terrible things Scott wants to forget. As he fights himself, struggling to repress his memories, Kim urges him to remember, otherwise he won’t be able to change. Eventually, he calms down, and simply stares at Nega Scott. Nega Scott disappears.

In addition to being a more satisfying moment of acceptance and change for Scott, this also parallels with Ramona’s need to stop hating herself and running away. Hey, our romantic leads have something explicitly in common. Go figure, any attempt at characterization at all can help a relationship in a story feel organic!

But with that realization, something else comes to mind: in the film we could criticize Ramona of being a manic pixie dream girl who only existed to continue making Scott’s life better no matter how much he messed up. But in the Scott Pilgrim comics, despite being fleshed out and a much more compelling character overall, Ramona ultimately serves a utilitarian purpose in regards to Scott…

She is the avatar of his emotions.

Put more plainly, in the story, Ramona represents Scott’s struggle to accept himself. We can tell this, because in the last pages of the book, they are describing the exact same struggle and bond over this. They both describe how hard it is to change, and how they can perhaps change together. And maybe, just maybe, Ramona taught Scott how to cha—oh god dammit we’re back to the manic pixie dream girl thing again, aren’t we!? Just executed more effectively!

It’s not just Ramona, either—female characters around Scott tend to just highlight a particular aspect of his personality or a character flaw. Envy is Scott’s shittier tendencies given form, literally saying the same questionable things Scott has (but a few pages later) so we know that Scott became an asshole because of Envy. Well, isn’t that great. Blame the lady. Characters even say at one point, “Scott was different before Envy.” Yes, breakups and bad relationships can be formative for the worse, and if there’s any environment to explore that idea, it’s this series, which is honestly all bad relationships and the fallout of breakups. (There were next to no battles. I was very much okay with this, as disappointed as say, Angry Joe might be.) But doing such a simple 1:1 with Envy and Scott feels… cheap.

Of course, it’s not just Scott Pilgrim that treats women as a catalyst to express the inner emotions of men. It’s most masculine art. Ever.

He looks unassuming, but we’re going to be talking about this asshole A LOT.

The Nightingale

John Keats was one of the most feminine-obsessed poets of Second Generation Romanticism while also being deathly afraid or in awe of women. Keats was a rather sensual poet, not just in the sense of sexuality but in how focused on human sensation he was—touch, smell, taste. And in almost all of his poetry these senses are overwhelmed by a higher being, whether it be Psyche, or the Nightingale, or La Belle Dame Sans Merci—and these forces are overwhelmingly feminine.

In his famous “Ode to a Nightingale,” Keats writes, not praise of the bird and its sweet sound, but a deeply anguished fall inward. Though he is addressing a creature of the stars and sky, one who is often a symbol of the Muse and upward transcendence, from the very beginning, he sinks deeper and deeper into depression.[6] “My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains / My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, / Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains / One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:” Note that, in the first few lines of the stanza, our titular Nightingale, the subject of this Ode, has not even been mentioned yet. Instead, the focus is on Keats, and implicitly, the Nightingale’s effect on him.

England, 2017

“Sometimes I wonder why you’re with me.”

“Because I like being with you. I wouldn’t be with you otherwise.”

“I can’t believe that. You’re too good.”

The Nightingale

In later lines, we see Keats’ drowsy, sinking affect take on a more urgent tone as he attempts to join the Nightingale in starry light… “Away! away! for I will fly to thee, / Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards, / But on the viewless wings of Poesy, / Though the dull brain perplexes and retards: / Already with thee! tender is the night, / And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne, / Cluster'd around by all her starry Fays;”

…only to stumble further into darkness.

“But here there is no light,”

“I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs…”

Philadelphia, 2017

Our last night together, waiting for a train in the dark. One of the few comfortable silences of the week.

“Your mother is going to hate me.”

“Why?”

“I’m going to hurt you. This is going to get so much worse before it gets better.”

“What if I’m okay with that?”

“You won’t be.”

The Glow

As Scott fights the Katayanagi twins, Ramona’s 5th and 6th evil exes, they shout at him that Ramona cheated on them, that her fear of Scott cheating on her is projection, that she’s likely packing her bags to run away again as they speak. As Scott reels from this information, Kim, who has been kidnapped by the twins and is currently trapped in a cage, performs the most selfless, noble act in the entire story. She opens her phone and yells to Scott, “Ramona just sent me a text. She can’t wait for you to come home. She believes in you.”

The comic panel shifts to Kim’s perspective. We see her phone. There is no text.

The Nightingale

It is near the end of the poem we realize that Keats is sinking, not just into depression, but himself, imprisoned by his emotions, specifically, “Forlorn.”

“Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam'd to do, deceiving elf.”

Despite his mind and heart’s greatest efforts, he recedes into his own ennui, cursing “fancy” (imagination) as a “deceiving elf,” who cannot cheat him away from himself. He cannot reach the Nightingale, yet he is also the one who has elevated the Nightingale to such a mythological, longing and yearning status to begin with.

Tereus, being a Nice Guy.

The poetic and emotional resonance of the nightingale as a symbol originates with Philomela. The Greek myth of Philomela describes her as a princess of Athens, brutally raped by King Tereus of Thrace. Afterward, he cuts out her tongue to prevent her from telling anyone what befell her. She weaves a tapestry, tells a visual story in order to get the truth out. Once Procne (Philomela’s sister) sees this tapestry, she murders Tereus’ son and feeds his son to him. In a revenge-filled rage, Tereus chases the sisters with an axe. In desperation, once Tereus has nearly caught them, Philomela prays to the gods to be turned into birds as to escape his wrath.

Philomela is turned into a nightingale. Procne into a swallow.

In nature, female nightingales are mute. Only the males may sing.

The Glow

Scott rushes back to Ramona’s place, only to see her already on her bed, dressed to leave with a bag packed. He says he doesn’t care what the Katayanagis have said, that people can change and she’s not a bad person.

Ramona insists otherwise, thanks Scott, and glows brighter than she ever has before.

When the light disappears, Ramona has vanished.

Boy, the artist really likes scantily clad women…

New York, 2019

Reading Scott Pilgrim is a bit like diving into your own personal romantic miasma.

Scott’s behavior, much like Rob’s in High Fidelity, forces us to examine our own, putting an unflattering mirror to the masculine condition. The dream-like, uneasy structure of the graphic novel reflects, not just Scott’s scattershot and unreliable memory of his actions, but the feeling any of us have diving a little too far in the deep end of our own worst memories.

Putting the book down for a moment, I had to just stand there and reel before walking downstairs to finish my laundry. As I stood bent over the stairway railing, I felt myself falling and falling, “Lethe-wards,” as Keats would put it, into memories from years past I swore I had digested and appreciated ages ago. I could see myself as a speck, drifting into a vast, tumultuous, black ocean of feeling, all summoned by one panel: an image of Ramona, lying awake in bed next to Scott, feeling—as the reader does—that dreadful distance, the one you love drifting further and further apart inch by inch. Remembering myself lying awake like that, being so close yet so distant to someone.

There’s another especially heartbreaking scene in the comic, where we see Scott losing his virginity to Kim in the back of a car. Kim, who we know Scott will soon dump unceremoniously as he moves away. Kim, who Scott won’t even remember most of the time afterward. Kim, who years and multiple heartbreaks later, will still have Scott’s back and try to save his relationship with another woman. As they curl underneath a blanket, she says, “Listen to this song. It’s a really good song.”

IN YOUR EYES

…directly referencing the sex scene from Say Anything, one of my favorite romantic comedies of all time, but in a much more painful context. One of Diane Court, the so-perfect-she’s-almost-boring woman having sex, not with Lloyd Dobbler, the best movie man ever (I’m just saying), but to Scott Pilgrim. An asshole. A guy.[7]

Diane often liked to say that we were like Lloyd and Diane in Say Anything. She said I was her Diane Court, this person she admired so much going off to England for a year. I remember upon first hearing that, thinking it was so sweet. And it was, obviously. But I also didn’t like being on a pedestal. I came to resent her for that.

But as time passes, I’ve come to think that she didn’t like being put on a pedestal either. And that I definitely put her there.

Seeing that throwaway reference in Scott Pilgrim just launched a flood of thoughts and angry feelings toward the comic. “How dare it subvert and take one of the sweetest romcoms in cinema away from me? This is so messed up to be referencing Say Anything in this context!”

But Say Anything, just like Aristophanes’ myth in the Symposium, may just be reaping what it sowed.

We’re Nearly Done, I Swear

Say Anything, among other things, was Cameron Crowe’s first directorial effort. More observant readers may have already noticed that this isn’t the first Cameron Crowe I’ve name-dropped and built my arguments on throughout this essay, too—he was the director and writer for Jerry Maguire and the less-fortunate Elizabethtown.

In Crowe’s filmography, there’s a very simple, singular, powerful ethos tying it all together, one that veers into saccharine naïveté at his worst and soars into endearing optimism at his best: he believes in the Platonic idea of soulmates. For example, he wrote Say Anything as a tribute to the first love of his life: “In many ways… Say Anything is a tribute to the first girl I really fell in love with… And yes, I used to drive by her house late at night, listening to music, feeling like a sap and somehow heroic at the same time. She was already with someone new, but I was going to wave the flag of our great love, even if I was the only one at the ceremony.” This idea of yearning is expressed in its simplest, most raw and powerful form with Jerry Maguire’s “You complete me.” It’s a line I have always loved while hating what it implicated, a sentiment that works so beautifully within the framework of the film but advances Neo-Platonism to unsuspecting moviegoers with that poisonous thought: “You are not whole. You are not complete. This hole can only be filled by another person.”

What sadder and more perfect culmination of this thought process is there than Elizabethtown,[8] a saccharine affair in which neither romantic lead is a complete character on their own, neither Orlando Bloom nor Kirsten “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” Dunst, but instead must form an amorphous, bland, romantic blob as one? And how perfect is it that the guy who most effectively argues for traditional “soulmates” in his movies is also the one who creates the most damning caricature of the concept?[9]

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, the film, cribs from Crowe’s worst work, while the comic intentionally subverts and challenges some of his best. It’s a weird connection to make, but it works. We can trace a line from Plato and Philomela, to Neo-Platonism and Romantic-era poetry, to Cameron Crowe, to every version of Scott Pilgrim, to Gamer-Gate, to our own (probably shitty) romantic experiences in life with a single idea:

Our idea of love itself, and therefore how it is represented in art, is inherently broken and robs women of agency.

The female nightingale is mute. Only the male sings.

Scott Pilgrim, as a comic, is so much better than the film, and I am grateful to have read it and for all the thoughts it provoked. I had a genuinely profound emotional impact from it that cannot and should not be undersold. It’s a great book. But that doesn’t avoid the ugly truth:

Scott Pilgrim only works as an exploration of Scott’s interior being. As romance, it’s paper-thin, but as an exploration of the angst of a deeply flawed 20-something dude, it works like gangbusters and captures those emotions perfectly. Ode to a Nightingale isn’t about a Nightingale, so much as it’s about Keats’ failed attempts to escape himself. Me writing about Diane, while it served many other purposes, also primarily conveyed what I —a white 20-something guy—felt in reaction to a lady. And at times, these all seem like generally smaller flaws in the grand scheme of things. Some would certainly say that these examples aren’t outright misogyny, at least. Scott Pilgrim isn’t “grabbing them by the pussy.” It’s harmless, let the gamer guys have their escapist fun! Let the guys write about their feelings however they want!

But see—these slights are only innocuous as long as people don’t try to escape them or remedy them. Sexism in games is no big deal, until someone has the gall to bring it up—then they’ll face a shitstorm of death threats and doxes and tweets and angry men saying “keep politics out of my games!” The role of women in the video game industry has been elevated enough that certainly we can stop talking about it, right until someone actually talks about it—in which case we get Gamer-Gate. The ingrained masculine perspective in art is fine and certainly slowly changing—until a few other perspectives are introduced and “oh my god aren’t there enough chick flicks already?”

But this is just how things are, right? How can you help what you feel toward the people you love, how can we re-examine centuries of romantic theory?

Just One More Reference

There’s a great scene in Don Quixote in which a man in a local town has literally died of a broken heart over a woman named Marcela. According to the townsfolk that Don Quixote and Sancho Panza speak to, Marcela is a cruel villainess, who has led the man on only to spurn his affections, and she should accept responsibility for his death.

Upon actually seeing Marcela, though, the pair see someone quite different. Marcela, about to depart into the mountains, lambasts the townspeople for their treatment of her. She says she informed the man over and over she did not love him, did not want to be with him. Her wishes should be respected as well, she says, as she wants nothing more than to live alone in the mountains as a shepherd. It was his doggedness, she claims, his insistence to suffer over her, for fear of not being complete on his own, that he died.

Conclusion

Contrary to what Plato once wrote in the Symposium, we are our own complete people. To delude ourselves into thinking otherwise is to lay down responsibility for our own happiness, an act of suffering. To enforce others into believing otherwise is outright cruelty.

Like Kim telling Scott he has a text from Ramona, Neo-Platonism and the idea that our soulmates are literally our other halves is a lie, albeit a moving one. But as sweet as it can be, it can lead to real toxicity, bile, and yes, suffering.

Unlike what Aristophanes told us, we can be our wild, four-armed, Greek, intersexual god-things. And once we realize that, maybe we can realize the most important lesson of all…

…

That Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is kind of a mediocre movie and we can do a lot better.

Me getting some damn sleep after finishing this thing

[1] In more detail: Aristophanes says that the halves of woman-women form “female attachments and friendships” (no homo) and that man-men have “pure and manly affection”, but, kind of adorably, “cannot tell what they want of one another” (NO HOMO REALLY). All you halves of man-women out there are SUPER SLUTS in Aristophanes’ eyes, though!

[2] Lord Byron’s favorite insult of John Keats’ perpetual boyhood in both temperament and station in life.

[3] Although I don’t think it’s a coincidence that next to none of Edgar Wright’s work has had any notable female romantic leads, aside from Liz in Shaun of the Dead.

[4] The film really is an expensive production of “Your princess is in another castle!”

[5] Inserting referential lines of dialogue that acknowledge how bad or strange a part of a story is, in an attempt to earn audience trust. See here, Linda Hamilton acknowledging the plot of The Terminator is absolutely bonkers if you spend one moment thinking about the time travel at the end of the film.

[6] Certain Deconstructionist critics like Paul de Man would like to say this is a failing on his part – that he attempts the visionary and falls into the melancholy. I believe the two are linked, and always have been.

[7] “The world is full of guys, Lloyd! Be a man.”

[8] Yes, Cameron Crowe later made Aloha, which is worse. We don’t talk about Aloha.

[9] Also worthy of note: Cameron Crowe’s most interesting film is also the most critical of putting others on a pedestal: Vanilla Sky. In it, Tom Cruise gets into a horrible accident, pumps up Penelope Cruz as the love of his life, but ends up being horribly (rightfully) rejected and sad for using her to prop himself up, and ends up escaping into a VR simulation of life (I am not kidding!) in which everything worked out how he wanted it to, but his own guilt turns the dream into a nightmare, much like the graphic novel version of Scott Pilgrim.

Tl;dr Vanilla Sky is really good and weirdly relevant to this exact paper and you should see it.