So, I saw Bumblebee recently, and if you want my tl;dr thoughts, I thought it was rather good. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it was fantastic, and it ended up being one of my favorite popcorn films of the year (in a crowded year, too). However, having seen it a couple times, I’ve started having some mixed feelings on its relationship to nostalgia, the ‘80s aesthetic, and how this relates to how we consume media in general. So weirdly enough, to truly communicate what I thought about Bumblebee, we first need to discuss…

Socrates. Huh?

Thrice Removed From Reality

In The Republic of Plato, Socrates makes the argument that art is an imitation “thrice removed from reality.” (Book X) The truest reality to Socrates is that of nature, landscapes, animals, and life itself, the gods being the most powerful crafters for this act of creation (an odd idea, but then again, The Republic is an odd book.) After this comes carpenters, artisans among humankind who are merely imitating nature, but bring forth something physical and useful to the real world. And then, there are poets, imitators of imitations, who arouse feeling but do not add anything tangible or substantial to our existence on Earth, and therefore should be shunned in his utopian State. “…he can paint any other artist, although he knows nothing of their arts; and this with sufficient skill to deceive children or simple people.” Driving the point home further in a far more candid and vicious moment, Socrates interrogates Homer, “If you are only twice and not thrice removed from the truth—not an imitator or an image-maker, please inform us what good you have ever done to mankind?... Once more, the imitator has no knowledge of reality, but only of appearance.”

Now, perhaps obviously as a guy what writes essays about art for fun, I have some grievances with this statement. While Socrates (or more accurately, Plato’s Socrates) is correct in how a painter can say, paint a blacksmith yet not know the first thing about sharpening swords other than the appearance of it, artists are still rather good at getting to emotional rather than literal truths. Even he implicitly acknowledges this as he launches a later assault on the poet’s ability to move audiences to emotion, discussing “…the power which poetry has of injuriously exciting the feelings. When we hear some passage in which a hero laments his sufferings at tedious length, you know that we sympathize with him and praise the poet; and yet in our own sorrows such an exhibition of feeling is regarded as effeminate and unmanly.” But, say we make the not-so-large leap that if a writer or poet creates a work that does align with our own feelings, our inner compass, or even change it for the better… then this is no problem at all. Thus, it’s tempting to say “why listen to Socrates at all?”

But we can’t. Despite these qualms, Socrates’ argument on art cannot be dismissed lightly. Believe me, I’ve tried. The truth is, some of the most valuable conversations about art come from understanding that it will be always true and deeply untrue at the same time. Movies can both ground us in ourselves and serve as an escape to different lives and experiences—often at the same time. That is one of art’s greatest powers, for better and worse (depending on the content). As long as that Feeling, that Tone of the film is correct, we will gladly accept these transformative journeys, no matter how far away they take us. And while not everyone experiences movies the same way, for most of us this has to do in large part with the Aesthetic of a film, and not so much what’s actually happening in the film. On top of this, we will easily let our own associated feelings with an aesthetic dictate our experience, rather than what that aesthetic truly represents, what darker connotations it may have.

Which brings us to a topic that I’ve been chomping at the bit to write about for some time now—the recent explosion that is the ‘80s throwback renaissance.

Can’t Stop Won’t Stop Never Stop the ‘80s

What is it about the ‘80s? Is it that a lot of filmmakers, music artists, and writers who were children then are now big enough names to contribute to the industry with what they know best? That audience members who grew up then are now old enough to be nostalgic, and this is all some kind of feedback loop? Is it that it’s an easy-to-replicate (if hard to truly master) aesthetic that stands out immediately, can be easily recognized, and adds marketability? Does this speak to some darker truth about some kind of nexus in our current culture, how our desire for escapism and rampant consumerism line up perfectly with our past selves from nearly 40 (40!) years ago? Or maybe it just looks and sounds cool?

This isn’t even a recent trend, either. If you think about it, we never, ever got over the ‘80s. Not even for a second. The ‘90s had a plethora of shows that looked and sounded exactly like the ‘80s—the ‘00s was already dipping its toe into nostalgia fare with films like Music and Lyrics, starring Hugh Grant as a washed-up ‘80s pop star, and the ‘10s… well, you get it. We’re there! And since The Guest, Passion Pit, Hotline Miami, Drive, and Stranger Things it’s been fucking non-stop.

So what fascinates us so much? It’s a weird choice for a decade to go gaga over. The ‘80s was a dark time in American history—the hope of the ‘60s had fizzled out to nothing, turned to the bleak soul-searching (and partial aimless disco hedonism) of the ‘70s, and hardened into a nihilistic, yet utterly cynical mindset of the entire culture. This was the decade of the AIDs crisis, of looming Armageddon at the hands of Soviet ICBMs, of economic deregulation… and yes, of Cindy Lauper and Tears for Fears and Molly Ringwald. It’s a weird split, right? Yet it’s one that is at best cursorily mentioned, if that, but never given deeper thought than that. And even as a failed business mogul from the ‘80s runs loose in the White House, a literal nightmare projection of the ideals of that era made real, we still don’t think about it. We don’t want to.

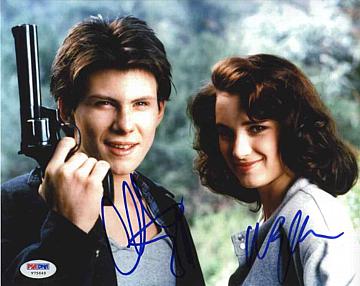

Just so we don’t dissolve into vagaries here, I’m going to discuss this split in the terms most familiar to me—I like to call this split of ‘80s identity the “Say Anything/Heathers Split,” both some of my favorite films of all time, for very different reasons. Say Anything, on the one hand, is the most wholesome romantic comedy I’ve ever seen, with the greatest male role model ever in John Cusack’s Lloyd Dobbler. It has a certain generational angst, an anxiety over what lies in store for all of our lives’ futures, but ends on the side of hope and selflessness. Then there’s Heathers, which out “Mean Girls” Mean Girls, cackling gleefully as teenagers viciously insult, stab, shoot, and poison each other, wearing a piranha grin like its titular Heather Chandler. It dresses up in a familiar bubblegum red and blue aesthetic, but reveals an aching nihilism, a cold void where its heart should be. One leaves Heathers feeling drained, and the only way to truly enjoy it is to be as cruel as its characters. So clearly, these films came out far apart from each other, right? This is some decade-long fall from grace?

Aw, what a cute pair of murderers!

Nope. Both came out in 1989. As a culture, we were feeling both these ways at the exact same time. Honestly, you look at the films and music of the ‘80s, and there’s no word for it other than “excess.” An excess of contradictory feelings, in overflowing, almost sickening quantities—of sincerity, of violence, of candy sweetness—all of it as loud and colorful as possible to hide a deeper vulnerability, fears too great to acknowledge, let alone confront. As another example, consider the defining sound of ‘80s synth pop—synthesizers. Now, synthesizers had been around since the ‘60s in some form or another, but they hadn’t caught on, for a kind of obvious reason—they sound cold. They’re scientifically, theoretically perfect sine and square (and many other) wave sounds that sound very odd, especially for the sound of the ‘60s. But they somehow found their way into the sugary sweet love anthems of the ‘80s. And as much as I love the sound, personally, they still sound incongruous. It’s artificial, cold, and in the right contexts sounds driving without ever necessarily getting anywhere. It again comes down to a split personality, which comes out in different ways only in the execution—we’ve got both Cindy Lauper and Annie Lenox here, remember.

It is in that split that I think we can start to figure out just why the hell we love the ‘80s so damn much. In the difference between the face it puts on and what it’s truly feeling inside, we subconsciously relate to it, to its yearning for forward movement or meaning, to its plight in stasis. It doesn’t hurt at all that it’s an easy aesthetic to enjoy, visually and musically, with a surface-level feel-good attitude that has a low barrier to entry—after all, “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.” Yet in either relating to the self-contained angst of the ‘80s, or more accurately, commiserating with it for too long, we end up exactly where we started: the art that Gets you, lets you know you’re not alone, becomes yet another voice in your head—companionship becomes solipsism. And I’m afraid that in continuing to just pump out ‘80s “feeling” movies, ‘80s “feeling” music, we’re subconsciously setting ourselves up to become more solipsistic than ever. It sounds so stupid and inconsequential, but I think there’s a great deal of cultural baggage left unexamined, and the more we continue to “unexamine” it, the more we enjoy stuff that makes us feel like what we maybe remember instead of confront what we’re actually communicating with our lionization of the time, the closer we get to some kind of meltdown of identity.

And in the middle of this fracas, right in the middle of my messy feelings on the ‘80s, on the value and hindrances of aesthetic, and on art in general, lies Bumblebee.

Yes, the Transformers movie.

The Aesthetic Choices of Bumblebee

At first, I wouldn’t have guessed that Transformers was going to hop onto the ‘80s train. In hindsight, of course, it makes perfect sense. Transformers come from the ‘80s, Paramount needed a new era to make a spinoff/prequel/possibility of ignoring the Michael Bay Transformers film, and again, people frickin’ love their ‘80s — have you seen the Ready Player One box office returns?

What is far more surprising is just how damn awesome the actual movie is. I loved it, almost the whole way through. Despite the core action of the film not interesting me at all—you know, what was before the main attraction to the series—I found something I would have never expected before; Bumblebee is, at its heart, a sweet coming of age story about opening yourself up to the world, about the bittersweet feeling of growing up, paired with the exhilaration of the limitless possibilities of early adulthood. In short, upon watching it, I felt it was made just for me—it felt like Say Anything did the first time I watched it, warm and moving and all-too-relatable (the Northern California setting did not help my feelings of nostalgia, having grown up there myself), and Hailee Steinfeld delivers an absolutely knockout performance once again as an aimless teenager, this time an 18-year old car nut named Charlie. (Also, if you haven’t, please please please check out The Edge of Seventeen.)

Having been blown away by it, I recommended it to everyone I could. Eventually, a friend of mine was willing to take up my offer of seeing it as I went to see it with him again. Enthralled that I got to have this emotional journey again, I settled into my seat before the movie started.

And then the movie wasn’t quite as good as I remembered.

It was still great, mind you. Just not quite as transcendent as I thought at first blush.

The majority of this can be blamed on what I implied earlier—that the movie’s main plot of Decepticons and Autobots fighting is a hell of a lot less interesting than the human characters and their relationship to Bumblebee, to the point that I actively wonder how much better the movie could be if we focused entirely on this E.T.-like story and not, y’know… Transformers. Put more nicely, the necessities of the Transformers brand put the brakes on an otherwise simple and resonant story. The real curiosity, however, was how this managed to slip past me the first time—and then the answer slapped me in the face.

On that first viewing, my primal, emotional reaction to the aesthetic and bildungsroman themes of the film outweighed the concerns of what was actually happening—where Socrates would make a difference between appearance and reality, with Bumblebee, the appearance became the reality, or, as I’ve been referring to them, the aesthetic became the content. And that’s why this is such a perfect, fascinating movie to talk about in relation to aesthetic theory and my thoughts on the ‘80s.

It is unsurprising that in this Hailee-Steinfeld-‘80s-bildungsroman-centric reading of Bumblebee, the first, most Transformers-centric 15 minutes of the film are absolutely the least interesting. On the plus side, this is the most comprehensible, entertaining action the series has ever had. On the down side, that’s not a high bar and still pretty much amounts to a lot of pretty clanging that, while I don’t mind, I also don’t really care about. Story-wise, the most important bits are Bumblebee’s traumatic injuries at the hands of a Decepticon removing his robot vocal chords, his memory loss, and the introduction of one John Cena as Gruff McMilitaryMan.

From his first moments on screen, the film establishes Cena’s character clearly as a self-aware, humorous, if still antagonistic military officer. Yet the couple of minutes of banter between him and his comrades before Bumblebee’s fall demonstrates a recurring move within the movie—have character traits that play against type while story-wise, be exactly that type. Cena certainly has charisma, and his scenes are all funny and appreciated in an otherwise rote role… but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a rote role. He’s an antagonist, someone to hunt down Bumblebee and Charlie, no matter the great character work they do to lampshade his trope-y part in the story.

The movie picks up significant steam with the introduction of Hailee Steinfeld as Charlie, however, immediately, almost jarringly shifting to the trappings of a high school coming-of-age film; Charlie is a disaffected teen dealing with the recent loss of her father, distant and disconnected from the all-too-cheery rest of her family, who often tell her, “why not just smile more?” and other wonderfully awful advice. She mostly stays inside her own world, listening to her Smiths-filled Walkman as she goes from an unsatisfying family life, to an unsatisfying work life, to her unsatisfying social life… you get it. The film cleverly reflects this “jukebox for one” theme as her scenes frequently have a smattering of ‘80s songs playing in the background, reflecting an individual curation and breadth similar to the soundtrack of a Cameron Crowe film. (Did I mention Say Anything yet?)

And as we see Charlie’s contained yet angsty internal world so clearly articulated, and the way her life’s soundtrack plays such a prominent role in this—for example, “Runaway” by Bon Jovi plays as she stares at the popular kids hopping into fancy BMWs and cars, belting, “…girls talk about their social lives / They’re made of lipstick, plastic and paint … All your life all you asked / When is your Daddy gonna talk to you / But we’re living in another world / Tryin’ to get your message through”—that I couldn’t help but think of how the “soundtrack of your life” idea only became possible in the ‘80s with the invention of the Walkman in 1979. Before, there were boomboxes, jukeboxes, and record players, sure, but these are all communal listening experiences. A boombox, though personal, broadcasts to the people around you; a record player is meant to be sat around and listened to together (the image of Beatniks passing cloves while listening to Miles Davis springs forth almost involuntarily), but portable headphones are for the Individual and the Individual alone, creating our own worlds… indeed, our own Life Soundtrack, as Cameron Crowe portrays implicitly in his films. Consider how even moments of intimacy with headphones, such as The Office when Jim and Pam share their earbuds, show less a communal experience, and more letting each other into their isolated internal worlds. For some, portable music is a convenience, but for disaffected teenagers such as Charlie, it is a lifeline, a personal air bubble that without which one would be miserable. Of course, as I have said before (and as I will continue to hammer at as many times as I have to in this essay), this lifeline can also easily become a lonely dead end, a solipsistic echo chamber of one. And at its best, Bumblebee uses its soundtrack to confront this idea head-on. For instance, I doubt it’s a coincidence that Charlie uses music to isolate herself, and Bumblebee uses it to communicate with others—though both uses fall under her vague statement, “Music can show how you feel.”

Really, isolation versus togetherness, the anxieties and comforts of both and the fraught relationship between them, are the engine of most of our romantic comedies, and despite Bumblebee not being quite a rom-com, it has the same dramatic questions. The emotional core of the story is not, “Will Bumblebee defeat the Decepticons?”—like I’ve said, that part’s kind of a drag—the core of the story is “Will Charlie reconnect with the world?”

In this context, Bumblebee reappears, as Charlie is a bit of a car nut who finds him abandoned and damaged as an ugly yellow VW Beetle. Being a teen who needs a car, she repairs it and takes it back to her house—only to have him transform into a god-damn ROBOT and understandably freak her out. Notice how even from the start of Charlie and Bumblebee’s arc, there’s a bit of a subversion here—the car is most often portrayed as a symbol and enabler of individual agency and freedom, and the story has certainly treated it dramatically as such so far. A car is Charlie’s ticket out of her family. Yet upon getting a car, we learn it’s actually a sentient robot, a friend—another potential community and relationship, the exact opposite of what Charlie wants (but what she needs, to use some Character 101 terminology).

As the two bond, Charlie soon puts a radio/cassette player in Bumblebee, and we get to the flipside of the whole ‘80s aesthetic thing. Remember when I said that Bumblebee at its best uses its soundtrack very purposefully, not for the mere sound and appearance of the ‘80s, but to communicate very basic ideas about the character and the era she inhabits? Well, as Charlie and Bumblebee goof around, we get a solid few minutes of the opposite end of this, which is a game I like to call “You Know This Song, Right?” First, she gives him a cassette of “The Safety Dance.” Then another Smiths song. Then, in a nadir, “Never Gonna Give You Up” by Rick Astley. Because, you know, Rick Astley? Like, Rick Rolling? Bumblebee just got Rick Roll’d! You know this! It’s funny! He spat it out immediately because he didn’t like getting Rick Roll’d! Many laughs are had by all.

Okay, so kind of unwarranted and venomous sarcasm aside, what I’m trying to say is that there’s a big difference in using your setting, music, and aesthetic to communicate something about the character (and in turn, parts of ourselves) and just using your soundtrack for cheap recognition laughs. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this, it just feels a little low brow for what’s been an otherwise very intelligent movie thus far. Look, I’m—I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed. It’s what separates this from say, Ready Player One, or Stranger Things season two, or most run of the mill ‘80s-regurgitations. And while it’s a blip in the movie, alongside an overuse of Judd Nelson’s famous fist pump from the end of The Breakfast Club, it reveals something a little uncomfortable for me, someone who really unapologetically likes Bumblebee, loves the ‘80s, and yet remains very exhausted by the whole nostalgia hubbub—even in Bumblebee’s smarter, more informed aesthetic choices, there’s a gut pleasure to it that has nothing to do with thematics. My pop-culture-addled reptile brain just gets a little hit of dopamine every time it hears synth-pop, or sees a clip of The Breakfast Club, or… or yes, sees a film with the same tone as my formative favorite Say Anything set where I grew up, amid Redwood trees and foggy beaches. Socrates would be rather disappointed, for in this respect, he is absolutely right—regardless of the reality of Bumblebee, its appearance gives me great pleasure. Thankfully, the reality of it is mostly great, if well-trod, but the realization still makes my stomach squirm a little. And everything I’ve been talking about—how the appearance can outweigh the reality, how Bumblebee’s aesthetic and thematic power uplifts an otherwise tried-and-true story, how nostalgia is its own force that, if called upon properly, will just emotionally melt the audience—it all comes to a head in just one scene.

A cute neighbor-boy named Memo comes into Charlie’s garage at the wrong moment and sees Bumblebee in not-car form, and from there the two start to bond as well. They go driving… in, with, can’t tell which word to use there—they drive Bumblebee around, and Charlie shows off how she can take her hands off the wheel and still stay on the road as Bumblebee drives for them. Her hands free, she pops off the sunroof, takes Memo’s shirt, blindfolds herself with it, and stands up with her arms stretched out, hair whipping in the wind. As Memo gets up as well, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” starts to play, a sunset on the horizon, seemingly endless rolling hills around them on the curving road as the camera pulls back into the air… it’s a beautiful shot, and a moment that tugged at nostalgic strings even I didn’t know I had. Nostaliga for young adulthood, feeling what those characters must be feeling—it’s a great moment of character empathy, which is only the most important goal in movies, to make us feel as the protagonist must.

And yet.

It’s a really bad use of “Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” Or a perfect one? Let me explain.

We’ve all heard it before, even if we don’t realize it. “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” by Tears for Fears is one of those songs that’s impossible to hear without going, “Oh yeah, THAT’S the ‘80s.” I personally first heard it in the ending credits of Real Genius, which just, in general, must be one of the most ‘80s films of its time. But it’s been used far more than that. It even appears in games like World in Conflict from time to time. And the purpose of employing it is singular, past even the meaning of the lyrics—it’s to communicate that whatever you are watching takes place in the ‘80s. And if it doesn’t, then it shares the same nostalgia and idealism for that time as you do, like say, In a World, an indie film with Lake Bell that ends on the exact same song.

And that cultural meaning, that broad shorthand and tugging of the nostalgic heartstrings has become so powerful that it’s easy to ignore what the song’s actually about. What is Tears for Fears actually saying? Like many songs, when you do start listening to the lyrics, it kind of sounds like nonsense at first. But let’s just type out the lyrics in plain English here.

Welcome to your life

There's no turning back

Even while we sleep

We will find you acting on your best behavior

Turn your back on mother nature

Everybody wants to rule the world

It's my own desire

It's my own remorse

Help me to decide

Help me make the most Of freedom and of pleasure

Nothing ever lasts forever

Everybody wants to rule the world

There's a room where the light won't find you

Holding hands while the walls come tumbling down

When they do, I'll be right behind you

So glad we've almost made it

So sad they had to fade it

Everybody wants to rule the world

I can't stand this indecision

Married with a lack of vision

Everybody wants to rule the world

Say that you'll never, never, never, need it

One headline, why believe it?

Everybody wants to rule the world

All for freedom and for pleasure

Nothing ever lasts forever

Everybody wants to rule the world

Wow. Out in the open like that, it’s kind of haunting, right? Paired with the bittersweet, distant synths and main guitar melody, this still sounds like a celebration, but a celebration of something about to disappear for good… “Holding hands while the walls come tumbling down / When they do, I’ll be right behind you / So glad we’ve almost made it / So sad they had to fade it.” I’m someone who, for fun, has tried coming up with every possible interpretation of these lyrics in his free time (really), so I mean it when I say there’s a lot of other ways to go with this too. There’s a simultaneous claustrophobic and expansive feeling here, as the singer is trapped by his “own desire” and “own remorse,” doing everything for “freedom and for pleasure” yet pleading with the audience at the same time, “Say that you’ll never, never, never, need it”—but what is “it?”

The contemporary listener wants to immediately jump to “capitalism”, which is valid, but it could also relate to that titular line that for some reason no one actually pays attention to—“Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” In short, it’s talking about our desires to “rule the world,” not literally, but individually, internally, controlling everything in our lives and being the master of our own destinies. But, despite our efforts, “Nothing lasts forever,” and “there’s no turning back.” In moments of loss, be they personal failures or relationships, all we can do is celebrate what was, move forward, and accept that while “Everybody Wants to Rule the World”—no one does. It’s a sweet-sounding song speaking of great loss and personal anguish, a perfect product of a decade that valued putting on a cheery face in the space of unspeakable tragedy—bubbly at first glance, but deeply melancholy just underneath the surface.

So, what the fuck is it doing in this scene in Bumblebee, other than to say “this is the ‘80s?” It works, I’ve already said as much, but why? Memo and Charlie have just met, certainly not about to have a bittersweet farewell. Bumblebee and Charlie aren’t departing either. It just doesn’t fit, and it comes really close to being as pointless a reference as “The Safety Dance” from earlier, just with more dramatic heft thrown behind it. It is a joyful scene with a song of loss playing in the background when no characters have experienced any loss. And while Real Genius’ end credits had no loss either, it had the benefit of actually coming out at the same time as the song did, reaching for a pop hit of the week while accidentally communicating for an entire generation, “this song is for happy moments, guys!”

But therein lies our answer.

In 1801, William Wordsworth wrote a Preface for his second edition of Lyrical Ballads, a collection of short poems written in collaboration with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In it, he declared his intent for his poetry, saying he was writing in opposition to excessive German poems of sentiment and near-Gothic levels of gore/tragedy meant to get as many feelings as possible. He then made the very famous statement that “Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” Other Romantic poets made similar sweeping self-appraising statements of their work—Keats said the poet had to be a “chameleon” in his letters, Byron bragged he could write hundreds of cantos of Don Juan right before his death interrupted this lofty claim, and Coleridge wrote several essays examining not just poetry, but nature and science as well. And for over a hundred years, English professors and scholars took their word for it and simply analyzed the Romantics and their work as they wished to be examined, the Preface and other primary sources taken at total face value with no critical eye to their intentions. It wasn’t until the ‘50s and ‘60s and the start of Deconstructionist theory in literature that someone thought to ask, “Wait, Wordsworth says he doesn’t like excessive German poetry—but doesn’t he literally write excessive poetry meant to provoke feelings himself?” For the longest time, the Romantics made their own narrative, and this led scholars into a dilemma where all they could talk about was this narrative.

We’re currently in a similar quagmire with the ‘80s, because the first decade to lie about the ‘80s was, unsurprisingly… the ‘80s. And from Real Genius onward, we have blindly accepted that “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” is a happy song, and that cultural misconception lets it work on the surface level for this scene. We see happy people, hear a happy ‘80s song, and it functions as we expect it to. But underneath the surface level of this joy, we see the rolling hills symbolizing endless possibility, the children on screen who remind us so much of our younger selves or who we wanted to be or wanted our childhood to be like, we see an era that never existed but for now, just now, we can pretend it did… and the whole melancholy nostalgia clicks into place in our subconscious as a flood of feelings comes out.

“Everybody Wants to Rule the World” doesn’t work in Bumblebee because it speaks to the characters—it works because it speaks to us. It is not their loss, but our loss of innocence, an innocence crystallized into the ‘80s era of music and filmmaking, that brings out so many feelings of joy and sadness at the same time, our adolescence more painfully absent for having been present for this short moment. There’s a reason nostalgia means both “homecoming” and “ache” in Greek.

It’s tempting to simply continue to revisit it. To dive deeper down the ‘80s hole, consume it faster than it can go away, drown ourselves in it. And there are plenty of movies and companies that promise this. The slogan for Mary Poppins Returns is literally “Magic Returns,” as if to say, “for over 50 years since Mary Poppins, your life has been meaningless and empty, but don’t worry, it’s back! For two hours you can feel like a child again!” It is this impulse that has led us to never truly let the ‘80s go, after all. But that cannot be sustained. And to disappear into our old loves and memories is to disappear into ourselves, removed from the rest of the world, when the answer is to take the feelings of our childhoods—the feeling of freedom, of hope, of romance and opportunity for change—and bring them to our lives here and now. The alternative is to be a slave to something sweet, yet ultimately unreal.

In Literary Theory, Terry Eagleton writes that it was only at the turn of the 18th century that aesthetic theory took on its current spiritual, ephemeral quality—the now all-too-common idea that some beauty resides only in the mind, that art turns to the immaterial. There were intellectual reasons for this move—putting everything into the mind reconciles certain artistic difficulties—but pragmatic reasons as well; in short, aesthetic theory became very interested in the immaterial at the same time underclass workers in the Industrial Revolution were very much concerned with the material. It was intentionally placating—culture and aesthetic beauty could be anyone’s, even if they couldn’t afford to feed their god-damn-family.

A similar trap lies in our current cultural state and the surge of ‘80s nostalgia. Just as Charlie overcomes her trauma and lets Bumblebee go at the end of the film, it is time for us to let go of the ‘80s. For good. Because, for all its rote character beats, its rare stumbling around intentions with aesthetic choices, Bumblebee ultimately makes incredibly intelligent use of its time period, and gives us a message we do not see from the films of that time…

If you love something, let it go.